Introduction

I have friends (and indeed a wife) for whom sport just seems like a silly notion – 22 blokes chasing an inflated bladder around a field – what’s all that about? But, for many of us, sport is a key part of our lives. It can be horrible- when my team loses I feel a real draining of energy and a sapping of morale. Over the years, I have been daft enough to follow some pretty unsuccessful sports teams, so that downer feeling is all too familiar. There is some chilling evidence linking sporting reverses with an increase in violence and domestic abuse. Sport is not always a power for good. So why is it so popular? I think there are several reasons:

- The drama is more extreme than any fiction would ever dare to be. Yes there are plenty of tedious and predictable outcomes, but so too there are outcomes so remarkable that no Hollywood producer would ever sanction such a story line.

- There is a primitive tribalism about supporting your team with a group of others. I almost used the word “like-minded”, but often we are not at all similar except for our shared passion. Chanting in a crowd is a thing of beauty, even if we are completely unreasonably questioning the parentage of the referee.

- The highs of winning in sport, especially against the odds, are better than almost any other high I have experienced. I can’t really explain that, but it’s true. I think I would get less from supporting a perpetually successful team. The New Zealand All Blacks expect to win every rugby game they play, so there is only ever a down side for them. No team I have ever followed has been even remotely invincible, though some have been reasonably successful for a short period.

Anyway, that’s why sport is a big part of my life. I have been lucky enough to have taken part in various sports over the years, but never to any great level. I am realistically more of a spectator. For most of my life, the sport I have watched and cared about was played by men. There were some honourable exceptions in tennis, and especially athletics (think Sally Gunnel, Jessica Ennis, Kelly Holmes and others) but it is predominantly team sports that really matter to me and the profile of women’s team sports over the years has been feeble. Why is that?

Women’s sport has had a pretty chequered history. In many cases, the misogynistic governing bodies, almost always made up of wealthy, retired, elderly white blokes, have been downright hostile to the idea of women even being allowed to take part in their sport. In other cases, women’s sport has been treated with patronising disdain. A few sports provide an exception, though often grudgingly. Many of the things I have to say about women participating in sports could also be said of ethnic minorities, but for the purposes of this blog, I intend to dig a bit deeper into the role of women in sport.

History

Sport has presumably been a part of the Human condition from the very earliest times when homo sapiens came into existence and quite possibly for neanderthals before that. I guess there might have been events and displays to establish the alpha male hierarchy and all of that. However, organised sporting events are most easily traced back to the ancient Olympics in Greece, which are known to have taken place as early as 776 BC and continued every four years for the next 600 years or more.

Those games were very male-centric, however. All of the competitors were male, but even worse, women were not allowed to even watch. Maybe that was because athletes traditionally competed naked. Imagine that with Linford Christie!

A caveat – I am not a sport historian and my big sister, who is, will probably be appalled by some of the over simplifications that follow.

Women were not allowed to compete even in the modern Olympics until 1920. Various bizarre reasons were cited, many of them pseudo-scientific, claiming that women, with their awkward reproductive systems and monthly cycles simply were not suited to athletic pursuits.

In the early 20th century, the mass exodus of young men to the world wars left huge gaps in western societies. Women’s suffrage is probably the most important advance to come from that period, but women also helped to fill the void of sport as a spectacle. In Britain, there were women’s football teams that attracted huge crowds. 53,000 seems to have been the most widely reported record in the early 1920s.

In the USA, there were similar tales, perhaps most notably chronicled by the 1990 film “A League of Their Own”, starring Geena Davis and Tom Hanks, which deals with a women’s baseball league during the latter half of WW2.

Hostility

Despite the popularity of women’s sport in the early 20th Century, the sporting authorities quickly mobilised to try to stamp it out. I’m sure there are many more examples of male hostility to women’s participation in sport, but I will highlight a few.

Football

It seems utterly incredible from the context of 2022, but the Football Association (FA) of England banned women’s football in 1921, stating that “the game of football is quite unsuitable for females and ought not to be encouraged.” Similar restrictions were imposed in other parts of the UK.

Many of you will have heard of Gail Emms. She is a fantastic athlete in her own right, having competed at Badminton in world championships and Olympics (gold and silver respectively). She is also a media figure and a regular contributor to radio shows like Fighting Talk on BBC Radio 5 Live. She was made an MBE in 2009. I’m no fan of the honours system, but this helps to build a picture of someone who has been successful in women’s sport.

What is not as widely known is that Gail’s mum, Jan, was an international footballer during the time of the FA ban. She was one of a team of women who ignored that ban and travelled to Mexico in 1971 for an unofficial women’s World Cup. Only six teams – Mexico, Argentina, England, Denmark, Italy and France took part. The England team had to do so without any backing from the FA and at their own expense. They lost both of their matches, but what an amazing set of rebels they must have been. The FA finally lifted the ban on women playing football on the back of this tournament, bringing to an end 50 years of misogynistic dictatorship. That does not mean they started to support women’s football – FIFA finally created an official tournament in 1991.

Athletics

In some respects, athletics (forgetting the restrictions of the early Olympians) has been more inclusive of women, but the record is far from clean. Some disciplines were considered too difficult for women. Even now, women have the heptathlon (7 events), while the male equivalent is the decathlon with 3 more events.

Much more jarring, however, is the history of the Marathon. One of the first women to challenge this assumption was Kathrine Switzer. She ran in the Boston Marathon in 1967, the organisers of which had just assumed that no women would dare to take part. The race director physically assaulted her when he realised that a women was competing in “his” race. I encourage you to follow the link above to see how that worked out for him.

Tennis

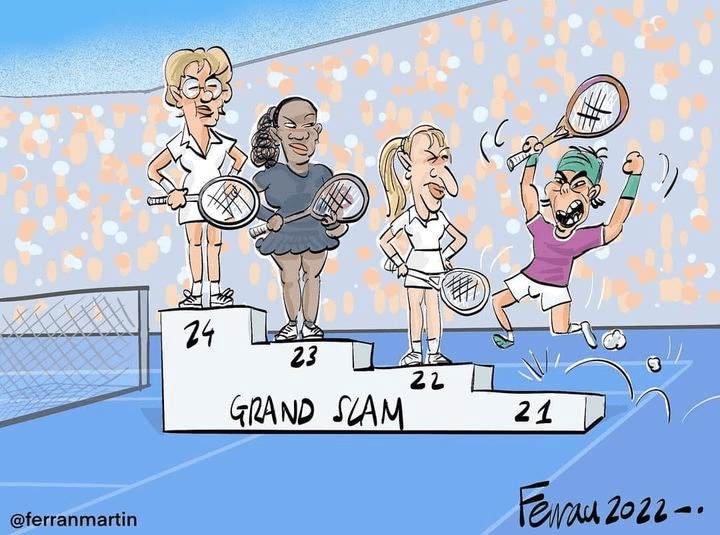

On the face of it, tennis is perhaps the sport where gender equality has been most readily adopted. There have been high profile women (or ladies as the tennis community would prefer) in the sport for longer than I can remember. I am just about old enough to remember Billie Jean King, but even before that there was Margaret Court and many others. Tennis it seems was the sport in which women could play and be taken seriously before almost any other. After Billie Jean King, there came the likes of Chris Evert, Martina Navratilova, Steffi Graf, Monica Seles, the Williams sisters, Venus and Serena and even a few British contributions with Sue Barker, Virginia Wade and most recently Emma Raducanu. This is far from an exhaustive list of women tennis players who have become household names.

I began this section with “on the face it”, and whilst there is no doubt that tennis has done better than most sports at encouraging gender equality, it has not always succeeded. Equal pay for both the men’s and women’s tours has long been a bone of contention. Back in Billie Jean’s day, the gap was at least ten-fold. It has closed since then, especially in the top tiers, with some of the majors offering equality.

There is a great article of pay differentials at adelphi.edu.

Tennis is not a favourite sport of mine, but I will continue with this because it is such an important example. Andy Murray is the most successful British tennis player for many decades. My Scottish friends point out that he is always Scottish when he loses and British when he wins. I’m Welsh, so amenable to such arguments, but that’s not the point here. Andy (and his brother Jamie, who is a highly successful player in his own right, especially in doubles) was coached by his mum Judy. Judy is clearly a very strong influence for Andy and Jamie. Andy has become famous for some particularly acerbic responses to interviewers that refer only to male tennis. Take a look at the following – honestly it will bring a smile to your face:

Cricket

My two favourite sports are Cricket and Rugby Union, so this is where | really get going. Women’s cricket was for years treated with disdain and contempt by a patronising misogynistic white middle class audience. The games lawmakers are the members of the Marylebone Cricket Club – the infamous MCC. They would not allow women to even join the club, excluding them from the pavilion at Lords.

The magnificent Rachael Heyhoe Flint (now a Baroness in a rather different Lords) was amongst the first 10 women to be admitted into the MCC in 1998. She was captain of England for more than 10 years and played for the national team for more than 20 years between 1960 and 1982. For many, even keen cricket followers like me, Rachael Heyhoe Flint was the only female cricketer we had heard of. She worked tirelessly and patiently to improve the profile of Women’s Cricket, often being subjected to degrading and insulting interviews. But, to some extent at least, it has worked.

Today the women’s game is in much better health. Several countries have a national team made up of full time professionals, with a professional league system backing up the national team. A big advance was made in 2021, with the introduction of the Hundred as a new format in Britain. I remain unconvinced of the need for a new format and I’m not sure the franchise system works in the men’s game, but there are some real advantages for the women’s game. The games are played in the same stadiums, back to back with the men’s games. Initially, you would see a small crowd at the start, gradually building as the start of the men’s game came closer, but as the tournament progressed attendances for the women’s game steadily climbed and it was obvious that many people were more invested in the women’s tournament. It was great to see mums and dads taking their daughters to watch the games and to see the daughters wearing the replica kits. That old adage of “You’ve go to see it to be it” surely means we have a generation of girls growing up to be the stars of the future.

Female cricketers are starting to become mainstream sports stars and amongst cricket fans, some have become household names. Retired cricketers, such as Isa Guha and Ebony Rainford-Brent (full name Ebony-Jewel Cora-Lee Camellia Rosamond Rainford-Brent) have been able to forge a successful career in the media as commentators and pundits for both the men’s and women’s games and have broken into the ultimate (though lovable) boys club – Test Match Special. The first woman I recall hearing on TMS was an attorney from Barbados called Donna Symmonds. She was brilliant and insightful, but the abuse she received for daring to commentate on men’s cricket is worth an article all of it’s own. Fortunately, there is one on Caribbean-Beat.

Rugby

Rugby has always been seen as a sport for tough, hairy alpha males and certainly in England (outside the south west, before my friends from Gloucester, Bristol and Bath start shouting at me) as the preserve of the public school educated. Against that backdrop, Women’s Rugby has struggled to gain the profile that we see in other sports, such as cricket and tennis.

There is now a professional system in England, but in supposedly rugby-mad Wales we are just starting to see a system emerge. In November 2021, the Welsh Rugby Union finally handed out 10 full time professional contracts. Ten! That’s not even a full team. TV coverage of the women’s game is sparse to say the least and there has been very little attempt to stage women’s matches at the same venue and day as the men’s matches. There have been a few attempts to do this in English club rugby, but more – much more – needs to be done.

In spite of this, women’s rugby still manages to produce some absolute superstars. I am going end this section with a bit of a celebration of one of them -Jasmine Joyce. If Jaz was doing what she is doing in the men’s game, she would be as the most famous person in Wales, but she has to play in England because of the lack of a professional setup in Wales. She has it all – pace to burn, determination, skill, elegance and brutality. She is lethal in attack, as shown in the following compilation.

But how about this for committed defence? I actually prefer this compilation.

Conclusions

I could go on forever – there are numerous sports I have not mentioned. Think of darts, where Farron Sherrock is now competing in what were thought to be men only tournaments. Think of boxing. I have previously spoken of my ambiguous and frankly inconsistent attitude to boxing. I will put my hand up and admit that I am too squeamish to watch women’s boxing, whilst my amygdala still seems to enjoy watching two men attempting to inflict brain damage on one another.

Anyway, I must bring this rambling to some sort of conclusion. Overall, I am optimistic about the future of women’s sport. Almost all sports seem to be going in the right direction, though some are much slower than others. I think (or is it hope) that there will be a virtuous circle that accelerates this process. The more women’s sport enjoys a higher profile, the more girls will see it and be encouraged to participate. Greater participation leads to still higher profile – onward and upward.

There are threats to that perhaps overly optimistic picture. The biggest threat is social media. We all know that social media is 90% toxic, but there are some trolls, keyboard warriors or morons – call them what you will – who seem intent on putting down women’s sport. Find any posting about women’s sport on Twitter and you will find a stream of dickheads commenting to the effect that they won’t be watching that. It’s bizarre – they must sit there in their squalid bedrooms all day searching for posts about women’s sport so that they can put it down. I hope and believe that this will be generational and that like all biases, this dislike of women competing in sport will fade into history, but I fear that will not happen fast. Those of us who love sport must fight for more coverage for women’s sport – it’s not enough to just passively enjoy it.

mber Sabina Park in the 80s. You could see your reflection on it. Pitches in the West Indies are now more like a long jumper’s sandpit. No wonder they don’t produce great bowlers any more. Who would want to bowl quickly on a beach?

mber Sabina Park in the 80s. You could see your reflection on it. Pitches in the West Indies are now more like a long jumper’s sandpit. No wonder they don’t produce great bowlers any more. Who would want to bowl quickly on a beach?

You must be logged in to post a comment.